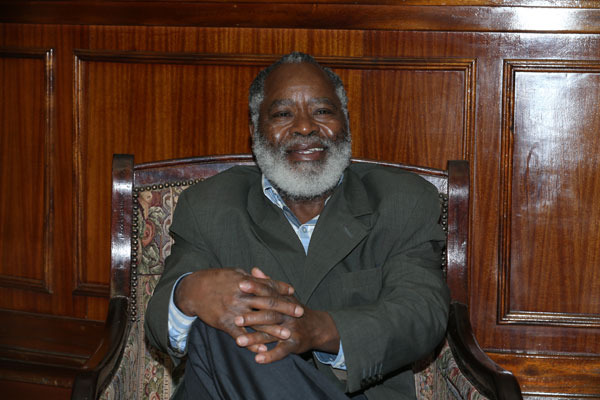

Kithaka wa Mberia is arguably one of Kenya’s best-selling authors with eight of his books having been approved by Kenya Institute of Curriculum Development (KICD) as study texts in schools. He narrates why he got into self-publishing, how to make money from books and how he’s helping fellow writers publish their works through his outfit, Marimba Publications.

Describe yourself and why you got into writing?

One element that humanises us and separates us from animals is our ability to change our environment. Creative writing is a way of chipping in or contributing in a modest way in improving society. You cannot divorce any form of art from entertainment, but entertainment cannot be the primary goal for my writing.

What is your favourite book and why?

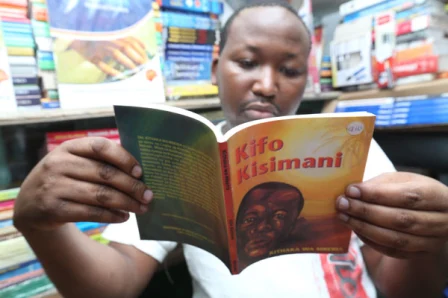

That is very difficult to say. It’s like asking someone who has three children, “Who is your favourite child.” My books are written for different purposes. Natala (1997) which became a set book in 2005 until last year, is about gender issues. Kifo Kisimani (2001) which was also a set book for seven years, deals with dictatorship. Flowers in the Morning Sun (2011) is about political clashes and also tackles the land question which is a big issue in this country. None of these issues is more important than the other.

There have never been tribal clashes in this country by the way. If the clashes of 1992, 1997, 2002 and 2007 were tribal, then logic dictates that the fighting would continue in intervening years, which didn’t happen.

The most dominant variable in these clashes is politics. I call them political clashes because they happen around the time of elections. Negative ethnicity definitely plays a role in the suffering of Kenyans, but politicians use it as a trigger to create clashes.

Given that you juggle teaching and running a publishing company, how do you find time to write?

I feel compelled to write and contribute towards improving society. There is a sense in which you can say my writing has a spiritual dimension. If you do something that makes people happy and improves their lives, God is happy with you. People talk about writing as being a mirror which you hold up for people to see themselves in it, but it’s much more than that. A good poet, dramatist or novelist goes beyond the mirror, not only painting the reality of society, but also making concrete suggestions for change. It’s not enough to say there is a lot of incest in this country. You must also prick people’s conscience so that they can protest and in effect deter or dissuade the next potential incestuous villain.

Why did you get into self-publishing?

First, I was using so much time and energy to write and wanted to have better control over publication of my own books. I was not happy with the first version of Maua Kwenye Jua la Asubuhi (1999) and very quickly removed it from the market and released a new version. I would rather recall a book and incur losses to ensure that what is out there is something that really portrays my wishes and aspirations. It’s very difficult to do that when you’re published by someone else because they are thinking about maximising their revenue.

One of the advantages of self-publishing is that you can control the quality of your books, and if something goes wrong, you can quickly correct it.

Second, people talk of self-publishing in a negative way and yet having your own studio and gallery as a painter is something that has been happening for so many years and we don’t frown upon that. Some musicians have their own music labels, we have scriptwriters who produce their own movies and nobody really sees anything wrong with that. But in the book industry, people always talk of briefcase publishers. Why can’t a writer publish his own works, so long as you’re not taking short cuts?

I started working on Rangi ya Anga, one of my poetry anthologies in 2006 and only published it in 2014. That’s how brutal I am with the control of my quality. Kifo Kisimani was put on stage for the first time in 1989, but every time I read it, I saw some weaknesses, so I reworked it until 2000. If I put my books side by side with those from bigger and more established publishers, you won’t notice any difference. I tell people; don’t judge a book by the publisher, judge it on its own merit.

I also wanted my books to be able to pay my bills. You can’t always be sure that publishing your own books will pay off, but when it happens, you’re better off as you get to keep more of the proceeds from sales than if you were published by someone else.

What are the challenges of self-publishing?

Marketing, distribution, selling and warehousing are not easy. It’s not all rosy.

Was it a challenge getting retailers to stock your books?

All the books I’ve written in Kiswahili (8 titles) have been vetted and approved by the Kenya Institute of Curriculum Development (KICD) and are in the Orange book (the official list of textbooks approved for use in primary and secondary schools). Kifo Kisimani and Natala were set books. The other six are listed as approved for use in schools as supplementary curriculum support materials.

This has helped to market the books. I also insist on the highest standards of binding (thread sewn section) and UV varnish covers. This ensures that even if a book falls on the ground or is handled by many people, the cover doesn’t become grimy. All my books are printed by English Press Ltd., the best printer in East and Central Africa, except one which I printed with another company. But I want to change because the quality is not that good.

How do you market your books?

I attend and exhibit at the annual Nairobi International Book Fair and sometimes go to regional book fairs. Being listed in the Orange book has also helped. Readers promote me through word of mouth such as writing reviews in newspapers and on the Internet. Even before Kifo Kisimani became a set book, someone had translated it into Italian. I also travel as an artist and academic and people get to know me and my books while on such journeys. I want to have some of my works published digitally this year and might also put some effort into marketing via social media.

Reasons for going into digital media (e-books)?

It’s a new frontier for doing business. I hope to attract more readers from outside Kenya, which is my main market currently. People won’t have to come here to buy my books, and I won’t have to worry about how to get a hard copy of my book from here to Moscow. People will purchase and read my books online on their computers from wherever they are.

Also, e-books will enable me to reach consumers directly and hence eliminate the need for two middlemen – the wholesaler and retailer who between them take 40 per cent of the retail price of a book. With e-books I won’t have to incur the cost of renting a warehouse to store the books, guards to ensure the books are not stolen and a driver to transport them to the market.

Which is your best-selling book?

The school market is the biggest market in this country for any publisher. So, if a book becomes a set book (compulsory reading for students) it becomes the bestselling book for that publisher. Kifo Kisimani was a set book from 2005-2012.

How many titles have you published under Marimba Publications?

I started the company in 1997 and financed it from my savings. I’ve published 28 titles; 13 are my own and 15 are English and Kiswahili texts by other writers.

How much money does an aspiring author need to publish a book?

That depends on various things. Number of pages, dimensions of the book, whether it has graphics/pictures or not, the printer you use, colour and weight of the cover, whether it has UV varnish, type of paper, whiteness and thickness, type of binding and number of copies. If you’re not taking short cuts and you want to produce a good book, around 100 pages, B6 size (125 x 176 mm), you need at least Ksh100,000-140,000 for one thousand copies.

How do you decide whether or not to publish another writer’s work?

I pay reviewers to evaluate whether a manuscript is good. If it’s acceptable, we sign a contract setting out the terms. We do not publish shoddy work; even if someone is willing to pay us to contract publish a book for them.

I once pulled a novel out of the market that cost me Ksh300,000 to publish and had it shredded because one bad book will hurt the reputation of the publisher.

If you bring me Ksh1 million and ask me to publish your manuscript and reviewers tell me no, I will not touch it because a bad book will affect other books and people will say Marimba is a useless publisher. If someone wants me to cut costs, I will also not do it because it has to be published to the same standard as I would my own books. If a book is poorly bound and falls apart, people blame the publisher, not the author.

How many employees does Marimba have?

I have a minimal number of staff, but most of the work is done by consultants such as accounting and audit, editing, layout and design. When I don’t know how to do something such as computing income tax, I hire an expert. I give them all the information on expenses and sales and they tell me how much I owe the Kenya Revenue Authority (KRA) in tax. Marimba is a fully-fledged company and I hired a lawyer to incorporate it because some people don’t want to deal with business names.

Any works in the pipeline?

By June this year, I intend to publish a poetry anthology. It’s just one poem, in Kiswahili, as yet untitled, which is more than 100 pages, tackling the issue of human rights. I will also publish another anthology this year comprising several poems inspired by my travel to various countries.

Who is your favourite author?

I focus more on poetry and drama. Some of the books that I loved a lot in the 80s were by Alexander Sergeyevich Pushkin. I read English, Kiswahili books and books translated from other languages. I watch theatre in different languages – Kikuyu, Luhya, Kamba, Gujarati, among others. I have sat in Germany and watched a play in the German language and others in Polish and Chinese while visiting Poland and China respectively.

A dramatist has to communicate with all the senses, not just the words. If you want to become a playwright, you must also be very conversant with theatre, not just drama. You need to watch as many plays as possible, both good and bad, to understand what works, so that you don’t make your characters do impossible things.

It’s about understanding changes of scenes to give characters enough time to change costume between scenes. Same with novels, don’t just read the best books. The bad ones will show you what doesn’t work.

What advice can you give aspiring writers?

Never take short cuts. To write you need to be informed and to stay informed. For that, you need a lot of information, data and research. For the poem I’m publishing this year on human rights, I started collecting data from newspapers and other media in 1991. If you rely on inspiration, you will only write one book and then dry up.

I watch news 365 days a year and try to get the story behind the story. I read other people’s works and not just literature. If you want to write a play on drug abuse, you have to talk to doctors, psychologists and drug users. It has to be authentic.

In writing, research is more than 50 per cent of the work. Good writers always immerse themselves in the experience they want to recreate in their books, plays or poems and their characters are often based on real people.

Bio:

Born: 8 August 1955. Married with two children.

Education: Chuka High School (O’ –Levels), Alliance High School (A’ –Levels), B.A. (Hons.), (University of Nairobi, 1979), M.A., (University of Nairobi, 1981) and PhD (University of Nairobi 1993).

Current job: Associate Professor, Department of Linguistics and African Languages, University of Nairobi.

Awards: Fulbright Scholar-in-Residence, Virginia State University, 2005/2006.

Publications:

Poetry anthologies: Mchezo wa Karata (1997), Bara Jingine (2002), Redio na Mwezi (2005), Msimu wa Tisa (2007) and Rangi ya Anga (2014).

Plays: Natala (1997), Kifo Kisimani (2001) and Maua Kwenye Jua la Asubuhi (2007).

Books translated into English: Death at the Well (2011), Natala (2013), Flowers in the Morning Sun (2011), A game of Cards (2011) and Another Continent (2011).

************

This article first appeared in the February issue of Sage magazine. All rights reserved. Please indicate the source when quoting this article.

Photos: Fredrick Omondi