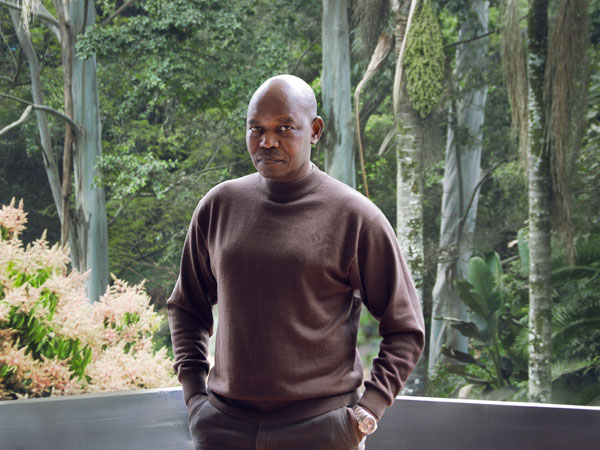

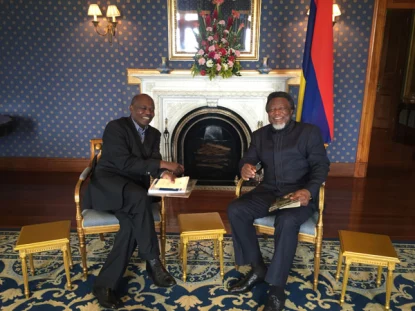

Wangethi Mwangi, former Editorial Director at Nation Media Group, and now Senior Advisor at African Media Initiative, shares insights on the biggest stories of the last three decades, his personal interactions with two Kenyan presidents and how the Internet is shaping the future of media in Africa.

By Wanjiru Waithaka

Photography: Emma Nzioka, AMI, Wangethi family

It was a bitter cold day with sheets of rain pouring down relentlessly. Warm air from the car’s interior fogged up the windows, matching the fog outside that had reduced visibility to just a few metres. The rain was a steady drumbeat on the roof as the car sped towards the coffee farms of Limuru, making good time on a road devoid of traffic, which had been cleared to allow passage of the president’s motorcade.

The late Juvénal Habyarimana, third President of the Republic of Rwanda, was in Nairobi on an official visit. Wangethi Mwangi, a trainee sub-editor with the Standard newspaper, was in a vehicle a few metres behind him, together with photographer Frank Wanjohi.

The motorcade had just passed the shopping centre at Banana when the storm felled a tree which hit electric cables, sending them crashing to the ground where school children waved miniature flags as they cheered the president. Three died on the spot. The Standard driver brought the car to a screeching halt at Wangethi’s urging as the rest of the motorcade sped on. Wanjohi leaped out of the car and began taking pictures, cupping the lens with his hands to shield the camera from the rain.

Wangethi started interviewing onlookers while taking down details of the scene. The police arrived soon after and the dead and injured were taken to Nazareth Hospital.

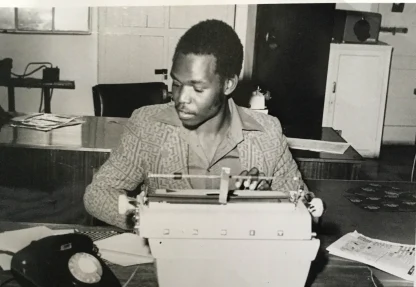

Back in the newsroom, he banged out his copy on an ancient type writer on six sheets of paper separated by carbon paper. The copies usually went to the news editor, chief sub-editor and the editor-in-chief among others. He pulled the sheets out of the typewriter, pleased with his handiwork.

His editor wasn’t impressed. He immediately put fresh sheets of paper into his own typewriter and taught Wangethi his first crucial lesson in journalism – how to write an intro. Wangethi had started the story thus: ‘Three school children were electrocuted yesterday…’. The editor typed: ‘Tragedy struck deep in the heart of Kiambu yesterday…’ and rewrote the entire first paragraph.

The story went to the front page giving Wangethi his first byline in the paper. A person unfamiliar with the workings of a newsroom would expect that Wangethi would be reprimanded for abandoning the Habyarimana assignment but instead he received praise for spotting a breaking story and following his instincts. After all, the paper could always use copy from the Kenya News Agency (KNA) for the Habyarimana story.

This was one of two incidents early in his career that shaped the way he approaches journalism even today. The other also involved a dignitary, but was the complete opposite of the stellar performance he displayed on the Habyarimana assignment.

The UN had just opened its Centre for Human Settlements (Habitat) office in Nairobi and Arcot Ramachandran, Under-Secretary General had been appointed its first Executive Director. The late Mitch Odero, news editor at the Standard, asked Wangethi to go to the airport and cover his arrival.

“Obviously, it was a big thing and yet I had no idea about Habitat and no time to research. He just gave me a car and photographer and asked me to go and report the story.” Wangethi racked his brain wondering how he was going to pull off the assignment.

“Calestous Juma, a reporter for the Nation, saved the day,” Wangethi recalls. Juma, now a respected professor at Harvard University, knew his subject. “He had studied a lot about the environment and was already acquainted with Ramachandran, so he fired all the questions while the rest of us took notes.” Juma wrote an excellent story for the Nation.

Wangethi describes his own story as passable. “I promised myself I would never go to an assignment unprepared, and would ensure anyone working under me was properly briefed before going out on assignment,” he says.

Meeting Wangethi for the first time is a confusing experience. His ability to smell a breaking story from miles away is legendary but he has a reputation for being a ruthless taskmaster who thunders when angry, is intimidating to his juniors and flat out arrogant even with superiors.

Managing editors who walked around the newsroom like they owned it, inspiring fear in juniors themselves, were said to be reduced to stuttering wrecks in Wangethi’s presence, almost as if their brains had been lobotomised or cloned such that they were unable to communicate in anything more than a mumble.

Kwamchetsi Makokha, a Nation columnist and communications consultant puts it thus: “With Wangethi, you have 60 seconds to make a good impression. If you don’t earn his respect when he first meets you, you’ll never earn it, no matter what you do in subsequent weeks, months or years.”

My first impression of him is a friendly social gentleman with a mild personality and not the least bit intimidating. Where is the monster I was warned about?

Wangethi laughs at this saying that is not his management style but when pressed, he admits there is some truth to it. “I was very demanding, very authoritative and also very impatient. That’s what I would call the extreme side of me, but if I liked you, I could be very patient, understanding and accommodating.”

He shouted when upset especially when someone goofed on a story. What is that common refrain ‘Lawyers jail their mistakes, doctors bury theirs, but journalists publish theirs for the entire world to see’? In such a high pressure environment where deadlines are critical, and reporters have only hours to put stories together, it’s perhaps understandable that an Editorial Director would lose his cool when errors slipped into the page.

After all, he was responsible for everything that went into the paper and was the one people sued when unhappy about a story. This sometimes extended to advertising where he was blamed when readers considered an ad offensive, never mind that ads were the preserve of the advertising department.

Wangethi also concedes that he can be very dismissive and has in the past denied someone a job in the newsroom or a promotion within a few minutes of meeting them. He says he goes with his gut and has no apologies about it. This confidence in himself, which has thrust him into leadership positions in his journalism career, has its roots in his childhood.

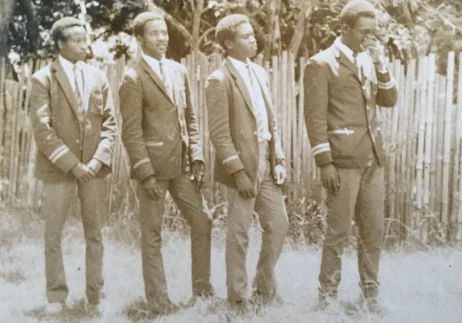

He was born in 1953 in Pumwani Maternity Hospital, the fourth born in a family of 10 children. He never met his oldest brother who died before he was born. The family lived in Shauri Moyo and later moved to Bahati, then Kaloleni Estate. In each of these places, the family lived in tiny one or two-roomed houses with communal bathroom facilities and a tiny kitchen that also served as sleeping quarters.

His mother, Salome Wanjiru, ran a grocery store at Burma market. His father, Geoffrey Mwangi, was a motor mechanic in downtown Nairobi. His two older brothers went to live with their childless aunt in Maragua, about 60km from Nairobi, where they stayed throughout their primary school education, leaving Wangethi in Nairobi with his four sisters, parents and paternal grandmother.

Wangethi would spend a week or two in Maragua with his brothers during the school holidays. Most of it was spent on his aunt’s farm, ploughing the field or picking coffee, which they took to the mill. He was a curious child and jiggers in particular fascinated him. “One day as they pulled out jiggers from my brother’s toes, I took a bit of it and pinched it in one of my fingers, and in time it grew,” he says. The subsequent itching sensation and painful experience of removing the jigger remain etched in his mind.

Christmases were spent in Nairobi. This was the one time of the year when their parents pampered them. “Dad would take us to the shops on River Road and buy us new outfits. Then we would have chapo, rice and meat. It was always an occasion to look forward to.”

Wangethi tried singing in the choir at Morrison Primary School and drama at Ofafa Jericho High School where he sat his O-Levels, but didn’t get very far with either, blaming it on sudden attacks of bashfulness.

“In Form 2, my teachers persuaded me to sing in the school concert. I got up on stage and started belting out Ob-La-Di, Ob-La-Da by the Beatles. After the first stanza, my voice cracked and I ran off the stage in embarrassment.”

He tried again later with better results. He was still in high school. His brother used to love dancing and would take him to daytime boogies at the local social hall.

“We went for one at YMCA Shauri Moyo and I spotted a friend in the band playing the drums. I asked them to give me a lift, that is, play a tune while I sang and belted out Wilson Pickett’s I’m a midnight mover. I couldn’t synchronize my singing with the instruments. They kept telling me to slow down and it was very frustrating, but I did finish the song and guys danced to the tune. Those were the days of soul music where you moved the upper body and shook your head vigorously almost to the point of dislodging it from the neck,” he says.

His older brothers being away in Maragua thrust Wangethi into a leadership position early in life. “Mum would wake up very early. I would escort her to the bus stop and make sure she got on the bus or matatu to take her to Marikiti where she bought supplies. Once in a while, I’d go with her, buy provisions for our store, and then we would head back home and wait for the mkokoteni (handcart) to bring them,” he says.

He learnt to cook at an early age. “I made tea in the morning for my sisters and learnt how to make chapo and other foods. During my university life, I spent holidays with my brothers and did all the cooking.”

With time, even his older brothers came to view him as the natural leader in the family, often deferred to him when family decisions needed to be made and left him to organise family gatherings. Wangethi knows what he wants and is not afraid to make a decision even if he risks offending members of his close family.

A good example is when he decided to legally change his name while in second year at the University of Nairobi’s main campus where he was doing a Bachelor of Arts course in literature and political science.

I decided this whole religion thing is nonsensical, baptism is just a form of cultural imperialism and I discarded my baptism name,” he says with relish. He hired a lawyer, filled out the required paperwork, which his lawyer sent to Sheria House and dropped the name Joseph by deed poll.

Did he consult his family before doing this? “I really didn’t care. It wasn’t their life, it was mine,” he says with finality. He attributes this decision to a Marxist phase he went through at the university, which he attended from 1973 to 1976.

“We were in this vice-like grip of militarism, engendered by the whole ideology of Marxism that was characterised by the conflict between capitalism and communism. Given our young minds, we were very easily persuaded to embrace communism. We felt for the rights of workers and mouthed catch phrases all the time to show how well read we were,” he says.

The university itself was going through a lot of changes at around the same time. “Scholars decided that we had read too much of English Literature, and therefore the emphasis ought to be literature in English, that is other forms of literature that are in the English language by people like Chinua Achebe and Ngugi wa Thiongo. That whole shift had a big impact on my mind.”

His parents had a customary marriage and later had an Anglican Church wedding at St Stephen’s on Jogoo Road where he was baptised. Wangethi later switched denominations to the Catholic faith after being influenced by his older brothers who were raised by a devout Catholic aunt. Thereafter he attended mass regularly at Our Lady of Visitation church at Makadara in Nairobi’s sprawling eastlands.

Then he discovered Marxism and threw away all that history along with his baptism name. It’s ironical though that for a man who professes not to be too hung up on religion, when he’s stumped by a question or is having trouble remembering something, his favourite exclamation is “Jesus Christ on a bicycle!”

Wangethi’s decisiveness extended to his marriage. Many girls dream about a white wedding but such whimsical notions never got a chance to take root in the Mwangi household. He met his wife Lizzie Wangui in 1974 while she was in nursing school at Nairobi Hospital. Lizzie was later employed as a nurse at The Mater Hospital. The couple had their first born, Mwangi, named after Wangethi’s father, while living in Buruburu estate in Nairobi’s eastlands. They had a civil wedding at the Attorney General’s chambers in Sheria House in 1981.

“That’s the one thing I had made up my mind about. I was not going to have a white wedding and had told everybody, including my parents. We got two witnesses, went to the A-G’s chambers, got married and then hosted a small lunch at Buruburu for our parents and friends.”

The couple have two other sons – Njeru, born in 1981, and Thuita, born in 1987. Mwangi lives in Sydney, Australia, where he works in HR. He is married with one daughter. Njeru is also married and has two daughters. Njeru and Thuita are both IT professionals.

Wangethi’s decisiveness sometimes got him into trouble however. Tragedy struck when the family lost three family members in quick succession. His father got a stroke in 1995 and was admitted to MP Shah hospital. “He had been suffering from high blood pressure and gout and was on medication. He was in a coma on life support for a fortnight and died in July 1995,” says Wangethi.

The family was still reeling from the loss when their mother was diagnosed with cancer soon after. “She had been complaining of pain in the stomach and I took her to a doctor in Kimathi House, who checked her out and recommended doing an endoscopy.” The results were grim. His mother was given six months to live.

“My dilemma was, do I share this with my brothers and sisters?” says Wangethi. “I decided not to, thinking I was saving them the agony of having to stare death in the face. They knew about the cancer diagnosis, but had no idea she had only six months to live.”

The cancer got really bad and she suffered. At one point she lived with Wangethi for a few months and then went to live with his older brother. When the cancer advanced to the point where it could not be managed from home, she was admitted to Equator Hospital in Nairobi West where she died in December the same year.

The family’s agony intensified when their eldest brother, Anthony Kamina, checked himself into hospital to have a nagging pain in his stomach checked. “Doctors opened him up and couldn’t deal with what they found; abdominal cancer that had just gone haywire. They closed him up immediately and within a week he was dead,” says Wangethi.

It was a terrible loss, coming so soon after the death of their parents. Much later, Wangethi told his siblings about their mother’s prognosis, that she had been given six months to live and he kept them in the dark. They were devastated.

They never forgave me. I told them I didn’t regret it, because I thought I was saving them this grief. But what happened, happened and I will live with that decision for the rest of my life.”

Wangethi’s journalism career began at the Standard newspaper, which hired him as a trainee sub-editor in 1977. He had responded to a job advert in the paper and was called for an interview where he found familiar faces also gunning for the job. He knew Absalom Mutere, Kamau Kanyanga and Mbatau Wangai, all from the University of Nairobi. Esther Kamweru, who had studied at Makerere University, was also at the interview. The paper hired all five of them. Wangethi’s salary was Ksh2,300 per month.

At the time, the University of Nairobi’s School of Journalism ran a two-year diploma programme for Form Six graduates. It was not a degree course but churned out some of Kenya’s best journalists. “In the morning, we would sit with the then director of the School, Bill Macketeer, in the Standard board room on Likoni Road and he would teach us journalism. Then we shadowed senior journalists like Gideon Mulaki and Frank Ojiambo in the afternoon as they did their rounds. We wrote a report after each trip, which was discussed the following morning during the training session,” says Wangethi.

The training ended after three months and Wangethi was sent to the news desk together with Kamweru and Kamau. That was when he landed the Habyarimana and Ramachandran assignments. Despite getting his byline on the front page a few times and winning praise for his reporting, Wangethi preferred sub-editing, which involved rewriting other people’s stories and never getting a byline in the paper.

I didn’t really like reporting and once I tasted sub-editing I realised that was my calling. The challenge of making something better appealed to me. I got the satisfaction of reading a story the following day and hoping that readers enjoyed it and although the reporter got all the credit, I hoped he was happy that I contributed to getting the story to the level that it actually excited readers.”

He stayed at the subs desk for a year then decided to enrol for a postgraduate diploma in mass communication at the University of Nairobi. Although his employer declined to sponsor him, he was fortunate enough to get a full scholarship from DAAD (the German Academic Exchange Service) with a monthly stipend of Ksh2,500. He graduated from the one-year course in 1980 with a distinction and returned to the Standard, which hired him as a Senior Sub-Editor with a monthly salary of Ksh6,000.

He did that job for only six months before leaving to join the rival Nation newspaper in the same capacity in November 1980.

At the Nation he found the no-nonsense English master Philip Ochieng, then chief sub-editor, who made him realise he still had a lot to learn about journalism.

“Working with Ochieng was a real shock. I thought I had honed my skills quite well as a sub-editor and reporter at the Standard. I had a BA in literature-in-English, so I knew my language very well. The first copy I edited and gave to Ochieng to revise was thrown back at me with red marks indicating errors here and there, and I looked at him and wondered, ‘Who the hell do you think you are?’. But I swallowed my arrogance and settled in, and realised that I had taken too much for granted. Journalism is not your usual English essay, it has its own style, and if you don’t learn it too well, you might end up not ever learning the craft as well as you should if you have the patience and the disposition.”

Ochieng taught him how to tighten copy, identify verbiage, trim a story without destroying its essence and introduced him to the Nation style of writing.

Wangethi rose through the ranks, earning promotions to deputy chief sub-editor, then chief sub-editor, managing editor of the Nation and eventually group managing editor in 1991. His promotion to GME came as a shock.

His boss, George Mbugguss, the GME, came into his office at four o’clock and told Wangethi that he and his assistant, Joe Kadhi, had been called to head office at Rehema House, next door to The Stanley hotel, by the executive chairman, Albert Aggrey Alexander Ekirapa, fondly referred to as “triple A”. “Around an hour later Mbugguss came back and called me to his office. We joked for a bit and then he said, “Wangethi, run the show. I’m out.”

“What are you talking about?”

“I’ve been asked to leave.”

“But you can’t just go, we have a paper to produce for tomorrow, we have all these things to do.”

“No, you run the show.”

“And that was it. That’s how he handed over to me,” says Wangethi. “I was stunned. I remember going back to my office and just sitting there wondering, what next? Where do I start? Do I continue working from my small office, which was right next door to his with a stinky toilet behind me, or do I go and sit in the big office? It felt very strange. Then I got a call from Rehema House. Ekirapa was on the line and he asked me to join him at his office.

“I was ushered in by his cheerful personal assistant, Violet Anyango, and for the next one hour, he briefed me about the board’s decision to change the editorial leadership. I’d take over as the Group Managing Editor with Tom Mshindi, who served in the role of associate editor, as the Daily Nation’s managing editor. ‘I must admit I was petrified and without thinking blurted out, “I’m not ready for this. I can’t do it.’”

“Don’t be a fool,” Ekirapa retorted. “You go and sit there and if you need any help we will be there for you.”

“This was around five o’clock and we had a paper to produce. The early edition had to go to the printer at 7pm and I didn’t even know what the top stories were. It was not that we were not used to this high-end of the journalism operation, no. It’s just that the hour was awkward plus the realisation that we were now the final arbiters in the editorial chain of command. If it had happened in the morning, that would have been better because we would have called our troops together and worked out a strategy.”

However, with only two hours to the deadline, Wangethi didn’t have much time to dwell on it. Everyone was looking to him for leadership and he had to step up to the plate. “I put away all my fears, called a meeting together, looked at all the stories that we needed to do, and we produced the next day’s paper.”

A typical day in the newsroom in those days started with a post-mortem meeting of senior editors at 11am. The team looked at all the day’s papers, including the competition and assessed what they’d got right, what had gone wrong and any scoops they had missed. This meeting was chaired by the GME and attended by the managing editors of the Nation and Taifa, the news editor, chief sub-editor, training editor and picture editor or chief photographer. The news editor took the team through the diary/docket to see which stories their reporters were chasing that day and what resources needed to be deployed in the field.

The team reconvened at 3pm to discuss the progress. By then, the news editor would have received the bulk of stories from reporters, which he would first assess to ensure they were newsworthy. He spiked those that weren’t by putting the paper through a sharp metal rod on his desk. These days such stories are simply deleted. The news editor would also take a first stab at cleaning each story to correct errors before sending it to the chief sub-editor, who would assign it to a sub-editor.

“The subs would panel-beat the story, decide where to place it in the paper with the guidance of the chief sub-editor, trim it to the desired length and choose any illustrations required,” says Wangethi.

Throughout this process, the news editor and chief sub-editor would be looking at the stories in terms of value to see whether they needed to put any one of them aside for consideration for the front page later in the day.

“We would look at these stories at the 3pm meeting and decide which was a good seller, hence meriting a front page splash,” says Wangethi. “Sometimes if a story wasn’t strong enough we added one or two other stories on the front page.”

The ingredients for a good seller were controversy, drama, scandal and tragedy. “During the early days of the Nation, accidents used to be very big stories. A road accident that killed 10 people was a front page story,” says Wangethi.

Parliamentary debates were also hot sellers because they allowed editors to craft sensational headlines like ‘Njonjo heckled in Parliament’ and the paper would milk it for days. “I look back at it and wonder, how cheap could we have been then? But the stories sold like crazy,” he says with a laugh.

Some stories were too hot or politically sensitive and had to be run by the editorial committee of the board – tasked with the application of the organisation’s editorial policy and guidelines – before being published. A typical example was the Anglo Leasing scandal during former President Mwai Kibaki’s tenure. “Because of the potential impact we thought it would have at the national level, with some people even suggesting it could bring down the government, we had to bounce it off the editorial committee of the board even though we had all the facts,” says Wangethi.

Stories about the 2008 post-election violence were also given the same treatment. Special Editions were another challenge. Sometimes a big story broke with no warning, requiring that a special issue of the paper be produced the same day. A good example was the August 1982 coup attempt by the Kenya Air force.

“Getting the teams together to do the Special Editions was always a challenge because we had to do everything at high speed while still making sure we had all our facts right. The government declared a 6pm curfew after the coup attempt so we were all rushing like mad trying to get content, edit it and then make sure it got out to Nation House on Tom Mboya Street and then Industrial Area where the printing press was,” says Wangethi.

At 3pm everyone was rushing to catch a ride in order to beat the curfew. Many people walked home because on some routes there was no public transport. “I was living in Buruburu then. It was crazy. Peter Mwaura (current Public Editor at NMG) was editor-in-chief and wrote the editorial aptly headlined The folly of a coup. Written against the deadline pressure of beating the curfew, it, quite understandably, ended up with lots of errors,” recalls Wangethi.

At 10.30am on August 7, 1998, Wangethi was in the boardroom at Nation House on Tom Mboya Street, interviewing job applicants. A sudden loud blast startled everyone in the room.

Wangethi, whose curious nature was still very evident despite rising to the highest ranks of a media house and doing what was essentially a desk job, immediately went to the window to try and pinpoint the source of the sound.

“Must be a tyre burst,” said one of the panelists. Not quite convinced, Wangethi abandoned the interview and ran outside to get a better look at the street. He saw wisps of smoke coming from the direction of Moi Avenue and people running in all directions. He took off with Frank Whalley, the training editor, close on his heels. Bits and pieces of paper from nearby buildings floated to the ground as they got closer to the Moi Avenue/Haile Selassie roundabout. They froze in shock on seeing the destruction of the Cooperative Building fondly called bell bottom because of its shape.

I couldn’t tell what had caused the carnage but remember seeing mannequins strewn all over the street and thinking, ‘Are those bodies?’” Then as the grim reality of the situation sunk in, with people coming out of the wreckage bleeding and screaming, their clothes in tatters, Wangethi quickly found the nearest phone and called Mshindi. “It’s not a tyre burst. We’re going to need a Special Edition.”

Having been the first on the scene, the pair went back to the office and wrote the lead story with Wangethi dictating and Whalley typing. “That may have been our last Special Edition. Television and the so called new media killed the Special Edition.”

Was there a story that left him vulnerable or afraid while on the job?

“Yes. I was managing editor, and Mutegi Njau was my news editor. We had just received a story about a minister against whom a warrant of arrest had been issued by the New York State authorities over some sexual misdemeanour, and decided to run it.”

At 7pm, the phone in the newsroom rang. At that time there was only one direct line in the newsroom, and it was on the news editor’s desk. Mutegi took the phone and then gestured to Wangethi to take it. “State House. Lee Njiru,” he said. Njiru was President Moi’s press secretary.

“I’ve been asked by mzee to tell you that the story that you’re planning to run on so and so, is not in the best interests of the nation,” Njiru said.

“Why not?” Wangethi countered.

“I am just telling you what mzee has said.”

“Well, I can’t pull out the story.”

“Is that what you want me to tell mzee?”

“You tell him what you want, but I just can’t pull out the story.”

Njiru hung up. A few minutes later the phone rang. This time it was President Moi on the line.

“Mr Mwangi ni nini hii nasikia?” (What’s this I hear?)

“Mr President, we have confirmed the story and the paper has already gone to the printer. And in any case, I’m not authorised to pull out stories once they’re in the paper.”

“Mr Mwangi, you are a young man, if anything happens to this nation, do you think your family will be spared?” Wangethi didn’t reply. “I’ve always said the Nation is Kenya’s public enemy number one, and now you have proved it.” The president went on and on complaining about the paper and then concluded by saying, “Anyway, I have said my piece, the rest is up to you.” Then he hung up.

Wangethi knew they had a good story of great interest to the public. They had checked all the facts so there was no risk of being sued for libel. Still he decided to consult his bosses. Mbugguss could not be reached but he managed to get hold of Ekirapa and explained the altercation with the President. Ultimately, the story was pulled out at great cost to the company.

The next day President Moi called. “Kijana, ulifanya kazi mzuri.” (You did well young man).

“I told him, it wasn’t my decision but that of my bosses.”

“Ulifanya kazi mzuri sana,” Moi repeated.

The matter didn’t end there though. Wangethi and Mutegi were hauled before a special committee of the board and interrogated about their conduct during the incident. “At the end of it, I was told in no uncertain times, never to engage the president in an argument. If he ever called again, I should tell him, ‘Let me refer this to my seniors,’ and then call either Ekirapa or Stan Njagi, the group managing director.”

He spoke to President Moi several times after that at State House functions, but they never clashed again. “Moi was very hands on and such calls to media managers were not unusual. Kibaki, on the other hand, was very aloof and rarely dealt with media directly. I only spoke to Kibaki once, and that was before he was elected president. He called me from the campaign trail and asked if I would publish an opinion piece he had written. I asked him to send it and we published it. We never met or spoke after he became president. If he had reason to complain about the Nation, he did it through other people, and if we had made a mistake, we corrected it,” says Wangethi.

In terms of openness, I think the media space expanded tremendously during Kibaki’s time even though it had started widening towards the end of Moi’s reign.”

One day soon after Mwai Kibaki was sworn in for a second term at twilight on 30 December 2007, Wangethi received a phone call from NTV journalist Rashid Juma, who had been deployed to Kisumu.

“Mr. Mwangi, I need your help.”

“What do you mean?”

“I’m in Kisumu. I’m running actually, looking for a place to hide.” Juma sounded fearful. The country had been on edge and the announcement of Kibaki as the winner of the election by the late Samuel Kivuitu, head of the now defunct Electoral Commission of Kenya, had set off a chain of violent tribal clashes in parts of the country.

“But Kisumu is your territory?” Wangethi asked Juma in confusion.

“I know you’ve always thought I’m a Luo, but I’m not.” And then he started crying. “I need you to help me. I can see these gangs coming after me.”

Wangethi quickly swung into action and mobilised a rescue team to extract the reporter but first ordered him to go to the nearest police station, DC’s headquarters or church compound and stay there until help arrived. In the days that followed more frantic telephone calls from their reporters in Kericho came in.

“We hired helicopters and sent them to Kericho and Kisumu, which were the areas worst hit by the violence in the early days,” says Wangethi. “We had to report on the chaos but for us safety comes first and we ended up flying some of our best people back to Nairobi, leaving our teams on the ground severely shorthanded. But I’m glad we didn’t lose a single soul in the violence.”

Back in the newsroom, things were unravelling fast. In previous elections, Nation staff always tried to maintain neutrality in their reporting, but this time around, cracks opened in the ranks as reporters and editors took sides, depending on which political party they supported – the Kibaki led Party of National Unity (PNU) or the Raila Odinga led Orange Democratic Movement (ODM), which had been declared the loser in the just concluded General Election.

“I remember Njeri Rugene, one of our editors coming to me and saying, ‘Hey, you better come down.’ She led me downstairs where our journalists were clustered in two groups before the two television sets in the newsroom, one tuned to KTN and the other to NTV, each showing a different region in the country. People were cheering and I wondered, what has happened to our newsroom?”

Wangethi was shocked by this turn of events. “I think the scale of violence just took everybody by surprise and people began to allow their emotions to take over. They lost all sense of objectivity altogether, so that suddenly you realised you are a Kikuyu or Luo or Kalenjin, and it affected the way you viewed the violence,” he says.

Wangethi at first tried to manage the situation by asking editors to remove all references to tribal or ethnic identity in stories and instead use ‘community,’ a euphuism that persists even today in reporting by mainstream media in Kenya.

He also asked to view footage of all NTV reports on the violence and insisted on edits where the station might be accused of fanning the flames. Needless to say that didn’t go down well in the newsroom and resentment towards him began to creep in. “I got accused of managing TV content to suit my tribal agenda and that wasn’t my intention. Our people brought back pictures and video footage of people waving machetes and screaming blue murder and I thought we just couldn’t air that; it will make things worse,” he says.

Suspicion and mistrust in the newsroom had grown to the point where even senior editors were accused of using their offices to further the agendas of their tribal chieftains. Photographers and sub-editors were not spared; the former accused of taking photos that showed only one side in good light and the latter of rewriting stories that completely distorted what the original authors meant to say.

I’ve never felt so helpless. Like you want your eyes to be everywhere in the newsroom because your forces are divided, but it was an impossible task.”

After days of reporting on the violence and media appeals to try and calm the nation, Wangethi felt so frustrated that he personally called the Minister for Internal Security, the late John Michuki and Isaiah Kabira, Director of the Presidential Press Service, to ask what they were doing to quell the violence. “Oh we’re doing something.” The vagueness of the response did nothing to reassure him.

Meanwhile, the perception among ordinary citizens was that the Nation had taken sides and supported Mwai Kibaki’s government. Its sales tanked to almost nothing in opposition strongholds like Nyanza. “That was one of the most trying times we ever had at Nation,” says Wangethi. “We hadn’t taken sides, but the perception was there and it took Nation a really long time to recover its position in Nyanza.”

Once the violence eased, his priority was twofold – get help in the form of counselling for staff traumatised by the whole experience and rally the troops to become a united front once more. “We needed to bring ourselves back to where we ought to be, where we had started, which is professionals that are bound by their duty or primary obligation to serve the public interest without any biases.”

For the entire media fraternity, not just NMG, what followed was a period of soul searching to determine what role media reporting had played in stoking tribal animosity in the months leading up to the election.

On 15 December 2010, Luis Moreno Ocampo the ICC prosecutor, called a press conference and named six Kenyans, three from each of the feuding sides, ODM and PNU, for sowing widespread violence following the disputed 2007 elections. The inclusion of Kass FM presenter Joshua Arap Sang among the “Ocampo Six” sent shockwaves across the media fraternity.

The idea that a reporter could be held personally responsible for his utterances and be hauled to an international court and not his employer was incomprehensible. It stunned many reporters who had assumed until then that you could always rely on your employer to protect you if people didn’t like what you said or wrote.

Wangethi has a different take on it, however. “I do not know whether Sang was guilty of what he was accused of or not, but one thing I know for sure is that he was thrown to the wolves by his employer to the extent that he couldn’t even afford a ticket to go to The Hague and had to rely on the generosity of the court to appear for his trial.”

“He was acting as an agent of the employer who should have taken up the case. Not sitting in trial on his behalf, but they should have put in place a proper support system for him. If, for instance at Nation I was sued for material that had appeared on TV or in the newspapers, I didn’t appear in court as Wangethi Mwangi, I appeared there as an agent of Nation and the paper paid all the legal fees.”

The impact of Sang’s arrest was visible in the way Kenyan media covered the 2013 General Election. “The media got a better sense of just how dangerous hate speech could be from the 2007/8 tragedy. And that’s what informed their coverage of the subsequent elections, consciously weighing the likely impact of the content of their stories and subjecting political utterances to rigorous vetting. There was a sense, an appreciation or acceptance that not everything that you see or hear ought to be reported and this led to more restraint by the media than before,” says Wangethi.

“There was also a very deliberate effort by the media to rely more on the electoral body’s vote tallying than on their own unlike in the past. “Every media house wants to be the first to report who is winning, but when you concentrate too much on numbers from a particular region and give the impression that somebody is winning because the numbers are high, without asking yourself, maybe we need to wait a little, and see what the numbers from this side are saying as well, that presents a huge problem.”

But aren’t media tallying mechanisms meant to provide independent verification of election results? “Media lost something of value there, all right, because when done well, internal tallying mechanisms provide a second perspective of what is happening on the ground,” Wangethi admits.

Giving the example of media in the west, such as CNN, which give accurate projections and even call elections in favour of candidates before the official results are in, he says that although Kenyan media played it safe in 2013, they should not abandon internal tallying mechanisms but instead focus on getting it right.

“Media in the US have their people at every polling station and they do exit interviews unlike here. They’re able to call an election based on the exit interviews. They’re better networked and funded. Our own pollsters still have a lot of deficiencies in the way they do their polling and that has affected the credibility of their polls. One way to enhance their credibility is to monitor how it’s actually done in the field to ensure their systems are sound; but then you need to commit a lot more funds.”

On Saturday 15 February 2015, Kenyans woke up to blank screens on four of the leading media channels – KTN, NTV, QTV (which has since been shut down) and Citizen TV. The four channels switched off their digital signals on DSTV, ZUKU and other pay platforms in protest at the way the regulator – Communications Authority of Kenya, was implementing digital migration.

It was the culmination of a long running battle as established media houses tried to protect their turf from the avalanche of new television stations expected after the migration from analogue to digital television broadcasting at midnight on 17, June 2015. The action by the four stations evoked mixed reactions. Wangethi believes that was a huge power play that backfired badly as it undermined the media houses in the eyes of the public.

It was very sad seeing men who were so experienced in the industry cutting their feet from under themselves the way they did, even agreeing to switch off their stations, and then very quickly realised, ‘What have we done?’ after the country just moved on.”

“I think the media believe too much in their power to influence and change things or resist things, and they don’t think there is a force that can bring them down to their knees, although that time they were proved wrong.”

He believes the three media houses didn’t handle digital migration very well. “Their language was very intemperate, ill-timed and arrogant. By the time they threatened to switch themselves off, I knew they had lost the battle to win over the public.”

Traditional media is still very relevant in the digital age despite the abundance of social media and citizen journalism. But it needs to stop competing with social media to break news and instead focus on what Wangethi calls Day 2 journalism.

“They should add value to stories by providing deep analysis and context, which social media doesn’t do well. A good example is Nation’s coverage of Jackline Mwende, whose hands were chopped off by her husband of seven years. They generated some very good packages on domestic violence, complete with statistics on its prevalence. There is a market for that because at the end of the day, readers want to understand why things happen,” says Wangethi.

He singles out mainstream media’s coverage of the Westgate shopping mall attack in 2013 for criticism, saying in their efforts to compete with bloggers who were providing first-hand accounts on the ground, traditional media houses forgot their role of fact-checking before publishing and resorted to peddling rumour as truth such as the hilariously ridiculous claim about a tunnel under the mall which the terrorists supposedly used as an escape route.

“They were sensationalising the event instead of giving context that would help people understand the story beyond just the headlines,” says Wangethi. “There is a hunger for that kind of content and people are willing to pay for it. Take a bit of time to ensure that what you put out for the public to consume is so tight and so well done that it enhances your credibility as a trustworthy platform for information.”

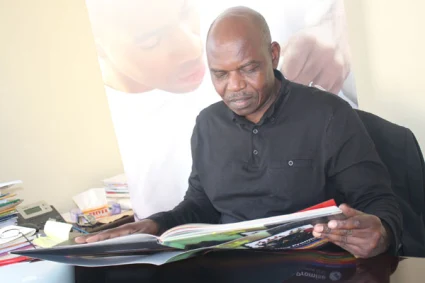

Wangethi retired from NMG in 2009 but stayed on for six months as a consultant to help organise a Pan Africa Media Conference, a joint initiative of NMG and the African Media Initiative (AMI), his current base. He is also still a board member of Mwananchi Communications in Tanzania and Monitor publications in Uganda, which are part of NMG’s stable.

After leaving NMG, he got together with peers to look at issues that affect journalists such as their safety and protection. Together with representatives from Twaweza Communications, Media Council of Kenya, Committee to Protect Journalists, Kenya Media Programme, Protection International, National Coalition of Human Rights Defenders and AMI, and with funding from HIVOS East Africa, they researched and produced a booklet Usalama Kazini, a safety guide for journalists.

The response was so good that they decided to include media owners in the initiative, producing a 10-point Charter to guide them on how to ensure the safety of journalists in their employ especially those deployed to war torn areas like Somalia.

Specifically, Wangethi was hired to breathe life into one of the pillars of AMI – ethical leadership and good governance within media houses. He researched the subject, supported by a team comprising media leaders from South and West Africa, drafted a set of principles and bounced them off media owners in Kenya. The resultant booklet, Leadership Guiding Principles for African Media Owners and Managers, was subsequently launched in Tanzania, west and southern Africa.

Wangethi also helps organise AMI’s flagship event, the African Media Leaders Forum held annually in different cities on the continent. The first event attracted only 10 participants but today is attended by over 600 media leaders, senior editors and reporters from across Africa.

AMI believes very strongly that media’s role is not just to play the watchdog role; but to play an effective role in the development of the continent by setting the agenda.”

“We have a programme called African News Innovation Challenge where we invite entries from journalists on serious issues like health, agriculture and climate change, which are not always sexy or exciting and so rarely make front page news. We then visit various capitals and engage with journalists to teach them how to write winning stories that they can sell to their editors.” This programme has taken him to South Africa, Morocco, Tanzania, Uganda and Rwanda.

Wangethi Fact file

Born: 1953

Academics:

Morrison Primary School (1960-66)

Ofafa Jericho High School: O-Levels (1967-70)

Jamuhuri High School: A-Levels (1971-72)

University of Nairobi: Bachelor of Arts – literature and political science (1973-76)

University of Nairobi School of Journalism: Postgraduate Diploma (1979-80)

Strathmore Business School: MBA in Strategic Management (2007-2008)

First job: Untrained Teacher (UT) at St. Philip’s High School at Kayata, Machakos

Loves:

Coffee. First thing he asked for at the photo shoot.

Favourite meal: chapati and beef stew.

Is a gym freak. Trains at Parklands Sports Club several evenings after work and weekend mornings. Also likes long walks (6km).

Typical outfit is grey or black sweater with tan slacks, large silver Seiko wristwatch.

Publications involved in:

- Media and the Africa Promise: based on speeches and presentations at the Pan Africa Media Conference held March 18-19, 2010 in Nairobi.

- Staying Safe: 10-point Charter for media owners, managers and editors to ensure journalists’ safety.

- A Protection Guide for Journalists in Kenya: A publication of the Kenya Media Working Group.

- Leadership and Guiding Principles for African Media Owners and Managers: A project of the African Media Initiative and endorsed by the African Media Leaders Forum in Tunis on November 12, 2011.e

- The Dar es Salaam Declaration on the Editorial Freedom, Independence, and Responsibility (DEFIR).

- Covering Outbreaks of Infectious Diseases: A Guide to Better Journalism: Lessons Learned from Global Coverage of the Ebola Virus Crisis.

This article was first published in the launch issue of Sage magazine. To read the rest of the magazine, click here.

All rights reserved. Republishing this article without permission from the author is strictly prohibited.